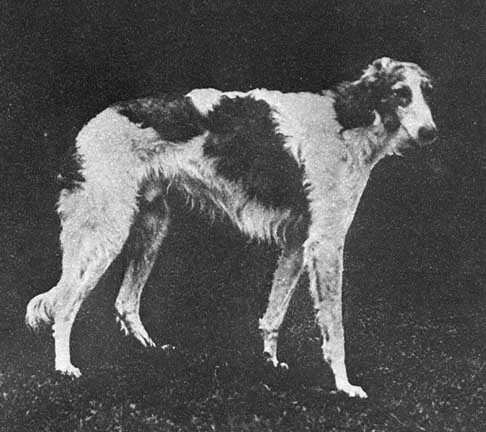

Udaloy 1876 (drawing) Argos 1892

"Style is not something applied. It is something that permeates.

It is of the nature of that in which it is found, whether the poem, the

manner, ... the bearing of a man. It is not a dress."

Wallace Stevens

The Borzoi coat is unique in the dog

world, not only in the delightful feel of its silky, thick, rabbit-fur-like

texture, but in its pattern of growth on the dog as well. Like most parts

of the Borzoi, the coat comes from function. The coat had to be warm, to

protect the dog in the cold of Russian winters; therefore it developed

with a plushy deciduous undercoat in winter. But the coat couldn't be too

warm, because on the other hand, the dog has to be able to dissipate heat

while and after running. Heat dissipation is a fundamental and primary

consideration for any athletic animal. This essential ability to dissipate

heat generated by running automatically imposes limits on both coat quantity

and body size; excessive amount of coat would be a serious, actually life-threatening

problem for the running dog. The borzoi coat developed to have a unique

pattern, with a thick protective neck mane of moderate length, longer thick

coat on the tail and back of the hindquarters for warmth and protection

when lying in the curled position in cold weather, and to be shorter on

the sides of the body to help prevent overheating when active. It is a

beautifully balanced fulfillment of required qualities.

The coat could not be too long, or of

a cottony texture, because if it were, it would pick up sticks and

other vegetation as the dog ran. An overly long or cottony coat would quickly

disable a dog in the field, tangling him into a thicket of useless immobility.

The wrong kind of coat can result in more than a few leaves in the feathering;

it can become an immobilizing disaster requiring gardening clippers and

scissors and significant effort to free the dog.

The coat should also be somewhat self

cleaning, so the mud of spring and fall will tend to fall off. These

requirements favored a coat that was silky, dirt-shedding, resistant to

matting in texture and of moderate length. The hunters of old Russia did

not want to spend many hours grooming their Borzoi, nor did they have the

blow dryers and coat conditioners and shampoos and grooming tables we have

today.

Their world left us with a wonderful,

unique, patterned coat, of moderate length, silky in texture with a thick

plush deciduous undercoat useful in winter and shed out in summer. This

close-fitting coat allows the beauty of the shapely borzoi body and it's

muscle definition to be seen. It is our good fortune that this coat also

happens to be one of the most pleasurable to the touch in the canine world.

Lucky us; beneficiaries of past pragmatism, we now get to touch that

delightful silky plushness. Fortunately, this unique original coat can

still be seen, and felt, today. But unfortunately, it is being displaced.

Excessive length and quantity of coat, coarse rather than silky dirt-shedding

texture, and the lack of a seasonal shed; all are to be found in borzoi

today; and all are alterations of the original silky, plush, patterned,

close-fitting deciduous borzoi coat. These alterations in the direction

of more, longer, coarser, and year-round parallel the increases in

quantity and loss of pattern the afghan hound coat has experienced. They

are all alterations away from the more specialized and toward the more

common and generic. Do we really want to trade in this incredibly luxurious,

plush, form-fitting borzoi coat for a coarse, generic, form-obscuring and

at times even sheeplike transformation? Do we really want our borzoi to

go the way of the afghan hound regarding coat?

If not, we need to pay some attention

to what we may be losing. Here are some descriptions of the Borzoi

coat.

"Complete Manual of the Coursing Hunt" by P.M. Giebin, Moscow 1891.

The Psovoi borzoi coat.

"Coat long, about 3 ½ in.; rather

thin, but soft, silky and glossy, and of the same

length on the neck, back and ribs. But

the ornamental hair is much longer-for instance,

on the edges of the hips it is often

7 in. long, hanging down in silky, wavy tresses, and

has heavy under hair. On the under side

of the ribs and on the belly it is thin and is

without under hair, and does not seem

so long, only toward the rear it reaches 4 ½ in.

The males have large side whiskers up

to 7 in. in length; the females lack these.

On the tail the hair is 5 to 7 in. long

and hangs down straight; the upper side of the

tail is covered with short, smooth hair;

around the root this is wavy.

On the hind edges of the forelegs the

hair is of the ordinary length of the hair of the

body, the fore edges as also the

head have a very short mouse-like coat of hair, but

it is also silky and glossy. In

general the hair on the Psovoi borzois is straight, wavy

or curly, according to which type of

its original progenitors the dog is nearer to, and

any of these is allowed as long as the

hair is not course and woolly, which would

indicate a crossing with common or sheep

dogs."

This is a very nice early description of what the Borzoi coat was and should be. The hair was 5 to 7 inches long on the tail and only 3 ½ inches on the body. Maybe we should specify maximum coat length in the standard.

Machevarianov 1876.

"The Psovaya

Borzoi has a thick wavy coat 4 to 5 cm

(1.6 to

2 inches) long, sometimes more, all over the body,

with long feathering as thin as ostrich feathers at the temples,

the rear sides of the front legs and the thighs as well as at the

lower side of the tail where it can reach over ¼ archin (7 inches)."

Machevarianov is calling for a shorter coat on the body than Giebin; only 1.6 to 2 inches. The feathering and the pattern are the same as described by Giebin and are distinctive features of the Borzoi.

Ermolov 1888.

"...the dog should be dressed in

a wavy, silky feathering. It is better if the cover

is not especially warm,

but with feathering of good quality."

Here Ermolov states that the coat should not be too warm, again because the running dog must be able to dissipate heat. An excessively long or heavy or unseasonable coat would be too warm, a serious disability for a runner who may overheat and suffer heat stroke if unable to dissipate heat.

Sabaneev 1892.

"Coat soft, silky and glossy; wavy in

places or in large curls all over.

The decorative hair, i.e. on the

neck, hips and tail, is considerably longer

than on the back and ribs; on

the head, from the ears forward, and the

fore edges of the legs, the hair

must be very short, like to a mouse, smooth and glossy."

Here no length is specified, but the pattern is described. This pattern is very distinctive to the Borzoi, and when coats become too long or excessive it is lost.

English Standard 1892.

"Coat - Long, silky (not woolly), either

flat, wavy, or rather curly. On the head,

ears and front legs it should be short

and smooth. On the neck the frill should be

profuse and rather curly. On the chest

and rest of body, the tail and hindquarters,

it should be long. The forelegs should

be well feathered."

American Standard 1905.

"Coat - Long, silky (Not Woolly), either

flat, wavy or rather curly.

On the head, ears and front of

legs it should be short and smooth;

on neck the frill should be profuse

and rather curly. Feather on hind

quarters and tail, long and profuse,

less so on the chest and back of fore legs."

The Modern American Standard.

"COAT - Long, silky (not woolly), either

flat, wavy or rather curly. On the head,

ears and front of legs it should

be short and smooth; on the neck the frill should be

profuse and rather curly. Feather

on hindquarters and tail, long and profuse, less so on

chest and back of forelegs."

The FCI standard.

"Coat: Hair: Silky, soft and supple, wavy or

forming short curls. On the head, the

ears and the limbs, the hair is satiny

(silky but heavier), short, close lying. On the

body, the hair is quite long, wavy;

on the regions of the shoulder blades and the

croup, the hair forms finer curls; on

the ribs and thighs, the hair is shorter; the hair

which forms the fringes, the "breeches"

and the feathering of the tail is longer."

All of these describe the coat pattern but do not specify lengths. They do state that the coat should be long. This is an arbitrary and relative description, and can lead to exaggeration as coats continue to become longer and longer. Further comment on the American standard will follow.

Galina Wiktorowna Zotova 1997.

"The Borzoi has a very specific

characteristic partition of coat: long, curly hair-dorsal,

long, thick

hair on breast and back. The flanks in contrary have very short hair."

Here again is a description of the coat pattern from a world-recognized Russian borzoi authority. When speaking about the differences between Russian and western Borzoi, Ms. Zotova said,

"Borzoi from Western countries

are much too large in height and the hair is thick.

The western people look

at Borzoi more or less as a decorative dog. So it seems

that they judge the dog

more in respect to exotic appeal than in behalf of the

correct anatomy, physically

ability and power.... Obviously, another difference

to our dogs, is the

long hair. That's western style and standard. So, some western

breeders say the Russian

Borzoi has little coat, although it is the original anatomy."

That is a succinct summation: a profuse coat

can hide an incorrect anatomy and a lack of muscular development and power.

It is also not "the original anatomy", that is, the breed's original coat.

Another change from the original hunting

borzoi coat involves shedding. Anna Shubkina, a Russian Borzoi

hunter, breeder and judge, wrote in the Russian PADS (the People And Dogs

Society) newsletter, in 2004,

"Hunting on Russian unlimited open spaces

did not allow the Borzoi to have too

heavy coat and the dogs shed strictly

according to change of seasons. Our Borzois,

as a rule, shed by the summer,

when they have a short light coat and develop a thicker

coat by winter reaching maximum

by late January-February. Showing dogs in Europe

requires a different kind of coat.

Since late 60th of the past Century, dogs with

luxurious heavy coat were consistently

winning and now, majority of the Borzois

in the West retain a heavy coat

during most of the year. Concentrated foods with

necessary vitamins and other supplements

stimulating growth of hairs and changing

the shedding schedule also helped

this."

Our interpretation is that alteration of something so physiologically basic as shedding cycles bears close scrutiny. In the desire to show a heavily coated dog year round, show selection is toward a dog that does not undergo a yearly shed. It requires a lot of protein and metabolic activity to grow a new coat, with as much as 25% of the protein intake being used for that purpose at the time of coat replacement. Selection against dogs who are capable of shedding out old worn coat and replacing it with new healthy coat is, inadvertently, selection toward a dog who is unable to bear the metabolic cost of coat production and therefore retains the old, worn coat rather than replacing it. In a genetic process called saltation, when one trait is altered, often other, unanticipated alterations ride along as well. These are unexpected by-products caused by the same genetic changes that were intentionally selected for when the single selected trait was altered. Saltations are why, for example, certain inherited diseases are evidenced by several apparently unrelated physical traits. Coat colors have been shown to be related to behavioral and reproductive changes in Dimitri Belyaev's studies of foxes. Temple Grandin has found evidence of hair whorls in cattle and humans being related to neurologic and behavioral traits. When we go about altering fundamental physiologic traits, we should be very humble and careful, because we may end up with associated linked changes we had no idea were genetically connected. And even on the simple face of it, causing dogs to carry a full heavy coat in warm climates throughout the year is a misery and a disservice to them.

The show Borzoi has, inarguably, gained

and changed coat over the years. The huge emphasis on hair for many

breeds at dog shows is apparent in the great deal of money and time spent

on hair care products and gadgets, for use inside and out. This goes

beyond presenting dogs with shiny clean coats; having a dog to show becomes

equivalent to getting a degree as a hair stylist. Borzoi coats with waves

or curls are often blow-dried straight for shows. Silicon spray is used

to replace the natural dirt-shedding silky texture. Supplements are sometimes

used not out of concern for supplying the dog with the healthiest possible

diet, but out of interest in growing the maximum possible coat. Less healthful

supplements have also been tried, such as low doses of arsenic, or thyroxin

given to non-hypothyroid dogs, in efforts to grow more coat. Perhaps we

should consider that the reason some of our dogs "lack coat" is because

massive coat was not what the breed originally had, nor is it the correct

and desirable coat for them to have now. Just imagine if this much emphasis

was placed instead on well-developed musculature and cardiovascular ability!

Fortunately for us, so far there are

still beautiful well-fitting silky coats to be found; they are not yet

entirely lost, though they are losing ground. The old curly and wavy coats

have been significantly reduced throughout the breed in the US, and

when the curls disappear, the waves will follow. The US standard still

specifies that the neck frill be "rather curly": it reads, "on the neck

the frill should be profuse and rather curly. Feather on hindquarters and

tail, long and profuse, less so on chest and back of forelegs". Keeping

less feathering on the chest and back of forelegs would be a great help

to the dog in the field, as well as maintaining a balanced, long-legged,

sighthoundlike appearance, and is in the standard for a reason; though

it's a reason we've long forgot, based in the field rather than in the

ring. Our first reference, Giebin in 1891 makes a point of this: "On the

underside of the ribs and on the belly it is thin and is without underhair,

and does not seem so long, only toward the rear it reaches 4.5 inches."

The words "long" and "profuse" are used in the US standard, but they need

to be interpreted within the context in which they were written.

Notice that the US standard from 1905

and the current one read exactly the same. Bistri of Perchino, whose photograph

taken in 1904 is below, was described as having a "magnificent" coat at

that time. As you can see, he would be described as lacking coat, today.

This is a great illustration of the fact that though the standard has not

changed one word on coat in almost 100 years, the dogs themselves have

changed a great deal. One point to take away from this is that written

standards do not preserve breeds in their original state; they only describe

what was within the context of their time, to those familiar with the meaning

of the terms when they were written. Following from this is that standards

need to be interpreted within the context in which they were written as

much as remains possible today.

Nowhere in the US standard is the coat

described as "flowing"; yet that description is commonly used as if it

were an attribute rather than a pejorative. "Flowing" goes in a category

along with other descriptors used by exhibitors as high praise but actually

found nowhere in the standard, such as "neck like a giraffe". A giraffe-necked

creature covered in a waterfall of hair cascading to it's ankles

springs to mind. These kinds of exaggerations and alterations, not described

in the standard, are not attributes.

A Russian breeder has explained to us

that the longest coat should be located on the tail, the back of the hindquarters,

and the collar, or neck. Under the chest is not one of the areas where

the longest hair is desired. If the borzoi has equally long hair

on the rest of the body, such as is appreciated in the west, it may be

considered a deviation from the standard and be penalized. It is more important

that the form of the coat be correct, with the fineness of hair on the

head and legs, than that there be a lot of coat. This fineness of hair

on the face and legs contributes to the dry appearance of the borzoi.

The "very short, like a mouse, smooth

and glossy" facial coat, "on the head, from the ears forward" specified

by Sabaneev in 1892 and others before him, is particularly aristocratic

in appearance, like silk, with the clearly apparent facial veins coursing

beneath it. When coats become too heavy, the face loses this fineness;

the veining is no longer easily visible, and the face toward the back of

the skull tends to grow longer coarser hair requiring trimming to comply

with the written descriptions of the coat. Very heavy coats also change

the appearance of the legs, obscuring the dry bladed shape and causing

them to look thick and heavy. Even the appearance of the feet is affected;

the detailing seen in a dry foot is no longer visible when the coat pattern

is disrupted and the hair on the legs is no longer fine, but thick and

coarse. The outline of the dog is degraded in other ways by excess coat:

the coat tends to become ill-fitting, with lots of hair lumping over the

hips as seen in the herding breeds; and huge coat causes a heavy, inelegant

appearance, skewing the visual balance of the center of gravity of

the dog and making it appear lower in carriage than it might actually be.

There are ample illustrations of the

original borzoi coat and it's variations, both in old photographs

and in old artistic representations, often depicting the curly neck frill,

like a muff around the neck, thick but not particularly long, and very

moderate coat on the rest of the body, sometimes even rather short, sometimes

curly or wavy, with only slightly longer hair on the tail and back of the

hindquarters. Shape-distorting masses of hair under the chest or

on the back of the forelegs are conspicuously absent, so the shapeliness

of the hound can easily be seen.

Excessive coat on the Borzoi is incorrect

for the breed and should be penalized in the show ring rather than encouraged;

it is naturally penalized in the field. Following

is a quote from The Onlooker dated 1891. "The proper and only 'true type'

of any breed is that which most exactly subserves the purposes for which

the breed is designed. Any malformation which is likely to unfit the dog

for its uses is fatal to its being true to type." This is the best

explanation of breed type we have yet seen; and though breed type and it's

common confusion with style are an entire topic in themselves, this quote

does put a fine point on the concept that excessive coat is antithetical

to breed type. In addition to historic loss and functional loss,

excessive coat also causes esthetic loss by obscuring the beauty of the

body, whose lines, curves, and proportions are the essential esthetic core

of the breed. As Wallace Stevens says in the quote used to open this article,

"Style is not applied. It is something that permeates. It is of the nature

of that in which it is found....It is not a dress."

The breeds we have inherited developed

by a dynamic evolution, but currently we seek to maintain them through

a static selection process. The real style is that of the body and the

mind inside it. It is based on behavior and physical and mental ability

over time, evolving in a multi-dimensional world. Voila; out of this process,

the form appears. Today, we have a very different selection method; a static

method, looking only with the eyes, at a brief, two-dimensional show ring

appearance, according to which we then live and believe and make

animal lives. When attempts at style are made by use of this two-dimensional

system, through exaggeration of single, superficial aspects such as coat,

the result can only be a sham, a caricature, a vaudeville show, tacky and

pathetic as pancake make-up. At it's worse, an overheating, sheeplike coat

can even make the poor borzoi, sadly, ridiculous.

They say a picture is worth a thousand

words, so below are many photographs of borzoi from the past. All are photographs

except for two illustrations, which are identified as such. Included are

several photographic examples from the country of origin taken at around

1900. Unfortunately, no photo seems able to illustrate the special, silken

quality of the borzoi coat; but we are able to see pattern and quantity,

though unable to perceive the texture. The photos are ordered chronologically

by year, starting with the oldest. Most of the dogs are named; some were

bred into the Valley Farm lines, such as Marksman, Bistri and Argos. Included

also are historic pictures of afghan hounds, for comparison to the modern

US afghan hound coat, as food for thought regarding the direction the borzoi

coat is to take.

The unique and specialized can easily

be lost, replaced by the common and generic. Do we want to discard

something as rare and beautiful as the borzoi coat, with it's derivation

firmly anchored in functional breed history, and change it with quick arrogance

for something as arbitrary and trivial as a dog show? The choice is ours.

.

Udaloy 1876 (drawing)

Argos 1892

.

Argos 1892

Leekhoi circa 1892

.

Modjeska

1894

Borzoi of Tsar Nicholas II, 1897

.

Daniar

1899

Marksman 1901

.

Borzoi in Russia circa 1900.

.

Bistri of Perchina 1904

Atamanka of Woronsova 1904

Described by Joseph Thomas as having a

Woronsova was known for its

"magnificent" coat.

profuse coats.

.

.

.

Westminster show 1909

Grenada of Perchina 1909

.

.

Circa 1909

Circa 1909 (painting)

.

Perchina

dog circa 1910

Perchina bitch circa 1910

.

1911

Perchina circa 1911

.

Rasboi o' Valley Farm 1912

Genest O' Russeau 1915

.

.

Cyclone of Perchina 1916

Ch. Soja 1922

.

1925 Mrs. Kent

Williams, TX

Square Acres Kennel N.J. 1925

.

Ivor o' Valley Farm 1926

1928 Kanza Kennels, KS

.

Nappraxin

o' Valley Farm and

Boi o' Valley Farm

Louba of Vladimir circa 1930

Best of Breed Westminster Show 1930

.

.

Pelleas of Perchino (an American kennel)

Afghans 1924

1933

.

Afghan 1933

Afghan 1933